The Australian government recently announced some changes to university funding arrangements [1], most notably among which is that humanities degrees will now cost AU$14,500 while “job-ready” degrees like teaching and mathematics will cost AU$3,700.

Table 1: Student and government contributions for university courses in 2021

| Band | Discipline | Cost to student | Cost to government |

| 1 | Teaching, English [including literature], mathematics, and postgraduate clinical psychology | AU$3,700 | AU$13,500 |

| Nursing and languages | AU$16,500 | ||

| Agriculture | AU$27,000 | ||

| 2 | Health, architecture, information technology, and creative arts | AU$7,700 | AU$13,500 |

| Engineering, environmental studies and science | AU$16,500 | ||

| 3 | Medical, dental and veterinary science | AU$11,300 | AU$27,000 |

| 4 | Management and commerce, arts, humanities (excluding languages), behavioural science (i.e. undergraduate psychology), law, economics and communications | AU$14,500 | AU$1,100 |

The stated aim is to guide students away from graduate-saturated professions like law to more “job-ready” areas where employment prospects are better. I’ll leave it to others to argue the merits or flaws of that aim. In this post, I want to address one specific argument against the government’s reforms: that a decrease in funding for university humanities departments and degrees devalues the humanities and necessarily diminishes the available humanities education. I will argue that universities are an extremely inefficient way of achieving accessible and high-quality humanities education and that Australia should instead consider adopting an Volkshochschulen adult education system, as used in Germany and other northern European countries, that includes humanities courses.

I’ll begin with two questions:

- Why should someone study the humanities at all?

- Why should someone study the humanities at university specifically?

The answers to Question 1 are (I hope) at least relatively clear: it enhances students’ capacity to think about abstract problems, it exposes students to a variety of perspectives (e.g. from other cultures, from other time periods, etc.) to which they would otherwise likely not have been exposed, it enables students to better understand their own culture and country and their place in it, it gives students frames to think about morality, and so on. All of these are absolutely important for citizens of a liberal democracy and I do not seek to denigrate any of them. More Australians should study the humanities. [3]

But the answers to Question 2 are not so obvious. A year-long reading group on classics of Western philosophy or an evening class on Aboriginal art would achieve the above goals as well as would a formal academic education. What university specifically adds is quite niche: it enables students to write extended technical essays on these topics, it situates students in the specific academic fashions regarding these topics (these change more often than the lay person would think, even for very old areas like Ancient Greek philosophy), and it establishes students on a pathway to becoming humanities academics. These ends aren’t unimportant, but they’re certainly not relevant to most people for obvious reasons.

Further, while university does not offer many unique benefits above and beyond extra-academic methods of studying the humanities, it does offer many unique costs. In the first instance, I’ll just note that universities are extremely expensive for both students and for the taxpayer. Under pre-reform student fees, a philosophy student would cost the government AU$6,116 per student per year, a sociology student would cost the government AU$10,821, and a foreign-language student would cost the government $13,308 per year. An ever-greater proportion of costs for these fields have been borne by students under successive government reform packages (see, for instance, new arrangements starting in 2007 [4]), so these numbers would be even higher under, say, inflation-adjusted 2005 figures (and they would be even higher again under proposals [5] of free tertiary education, in which the government would assume the full cost). This is similar to the amount the government spends per primary school student (AU$12,604 in 2015 [6]), and they are monitored continuously for 6.5 hours of the day!

Table 2: Student and government contributions for university courses in 2020

|

Band |

Discipline |

Cost to student |

Cost to government |

|

1 |

History, archaeology, indigenous studies, criminology, English, linguistics, philosophy, religious studies |

AU$6,684 |

AU$6,116 |

|

Behavioural science (i.e. undergraduate psychology), sociology, anthropology, gender studies, social work |

AU$10,821 |

||

|

Clinical psychology, foreign languages, visual and performing arts |

AU$13,308 |

||

|

Nursing |

AU$14,858 |

||

|

2 |

Mathematics, statistics, computing, building and architecture, community health, other health (e.g. massage) |

AU$9,527 |

AU$10,821 |

|

Allied health (e.g. pharmacy, optical science, etc.) |

AU$13,308 |

||

|

Science, engineering, or surveying |

AU$18,920 |

||

|

Agriculture |

AU$24,014 |

||

|

3 |

Law, accounting, administration, economics, commerce |

AU$11,155 |

$2,198 |

|

Dentistry, medicine, or veterinary science |

$24,014 |

I’m certainly not the first person [8] to make this point, but this is an insane amount to be spending on a humanities education if we mostly care about making sure that Australians are well-educated in the humanities. Further, a lot of this money does not go to teaching the humanities at all! Much of it funds the substantial bureaucracy of universities (ask yourself, why do not-for-profit public universities need marketing departments?), and a large amount (i.e. in the billions) cross-subsidises academic research [9]. Tutors have to be paid to mark essays and exams—even if (as I argue above) these essays and exams are sufficiently technical and academic in nature that they would not likely contribute to the holistic aims of a humanities education. All of this adds up to a hefty sum.

There’s another unique point about a humanities education at universities: it’s very hard to do alongside full-time work or training. Some more vocationally oriented courses (for instance, law masters’ degrees) offer weekend intensives or evening classes, but lectures and tutorials for more traditional humanities courses fall almost exclusively in business hours. Needless to say, this makes it difficult for an electrician or a nurse to study the humanities at university, even though we certainly want to offer them the opportunity of a high-quality humanities education (a major point of a humanities education is that it is not meant to be limited to the aristocratic classes!).

This isn’t to say nobody should study the humanities at university—aspiring academics certainly should, as well as any who want to “get into the weeds” of academic humanities research. But most people don’t need or want to write a dissertation on Norse influences on Shakespearean neologisms—they just want the capacity to discuss and think more deeply than is generally possible in the prosaic world. For these people, I propose that we seriously consider the northern European model of Volkshochschulen.

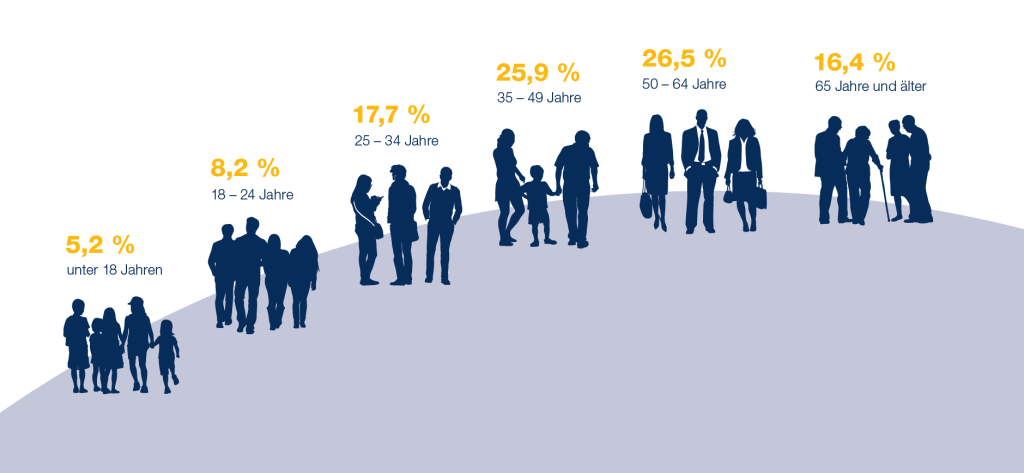

Literally translated as “people’s universities”, Volkshochschulen are amped-up adult education institutes [11]: in addition to the standard adult-education offerings of school-leaving certificates and integration courses for recent immigrants, Volkshochschulen offer a variety of courses in social and political topics, art, foreign languages, and health. Set up in the early 20th century to enable all classes of society to enjoy the benefits of a humanities education, Volkshochschulen in German enjoy heavy subsidies such that term-long courses can be taken for roughly €20. So, instead of nurses’ or electricians’ having to go down to part-time hours or take extended leave if they want to study literature, they could take a term-long evening class on Austen for the price of an expensive dinner. Given this, it is perhaps unsurprising that Volkshochschulen observe a much broader age range of students than do humanities courses in Australian universities. There is genuine life-long engagement with deeper questions.

Even at German levels of government subsidy, Volkshochschule courses would be much cheaper to run than courses at a university. You could conceivably hire a literature PhD graduate at AU$100k p/a to teach five different literature evening courses and this would still only amount to the same government subsidy as ten sociology students at university. This is an oversimplification—there are overheads, of course—but it is not a ridiculous one. Even accounting for some overheads, there is every reason to assume that a wide variety of courses could offered at minimal cost to the taxpayer in a way that basically all taxpayers could actually enjoy. Due to these low costs and the fact that courses do not need to count towards a degree or some pre-specified learning objectives, Volkshochschulen can be scaled as required for community needs and desires, as has happened in Germany. It would be difficult to justify establishing a Department of English Literature at the La Trobe University campus in Mildura, but there’s no reason to assume an ad-hoc Volkshochschule couldn’t run courses in literature out of the town hall.

This argument of “hurting humanities department is a rejection of the humanities” therefore needs to die. Humanities departments in universities are neither the only nor the best way of providing a humanities education. They are extremely expensive, the specific content is in most cases too technical, and they are hard to access unless you’re an 18–22-year-old with no dependents or other commitments. Volkshochschulen offer a flexible, scalable, and efficient alternative.

[1] Conor Duffy, “University fees to be overhauled, some course costs to double as domestic student places boosted”, ABC News, 19 June 2020, link

[2] Department of Education, Skills and Employment, “2021 allocation of units of study to funding clusters and student contribution bands according to field of education codes”, 26 June 2020, link

[3] There is another, more instrumental, argument that is often deployed for studying the humanities: namely, that it improves one’s ability to communicate. I am profoundly sceptical of this argument. In the first instance, the feedback given on essays is often minimal at best and largely relates to argumentation, not expression. Further, and purely as anecdotal evidence, I formerly worked as the editor of a policy publication and managed a team of sub-editors, who were mostly students—often top-performing ones. Almost invariably, law and humanities students were the worst editors by a substantial margin. It may well be true that many good writers enter the humanities, but I would refute any claim that study of the humanities causes an increase in writing quality.

[4] Department of Education, Skills and Employment, “Indexed rates for 2007”, 11 December 2013, link

[5] Fergus Hunter, “Free university and TAFE under ‘transformational’ Greens education plan”, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 December 2018, link

[6] James Mahmud Rice, Daniel Edwards and Julie McMillan, Education Expenditure in Australia, Australian Council for Educational Research, 2019, link

[7] Department of Education, Skills and Employment, “2020 allocation of units of study to funding clusters and student contribution bands according to field of education codes.”, 18 June 2020, link

[8] See, for instance, Tanner Greer, “Modern Universities Are An Exercise in Insanity”, The Scholar’s Stage, 14 January 2018, link

[9] Andrew Norton, “The cash nexus: how teaching funds research in Australian universities”, Grattan Institute, November 2015, link

[10] SMBC Comics, “College-Level Mathematics”, link

[11] “Volkshochschulen: Zahlen, Daten und Fakten über Deutschlands größten Weiterbildungsanbieter”, Deutscher Volkshochschul-Verband, link

[12] “Volkshochschulen: Zahlen, Daten und Fakten über Deutschlands größten Weiterbildungsanbieter”, Deutscher Volkshochschul-Verband, link